DARPA_Big_Data.jpg

A casual reader picking up a magazine talking about citizen science learns that it is some kind of scientific work done with the participation of the general public. Work that frequently takes place in collaboration with professional scientists and research institutions. A citizen scientist, he finds out, can be a member of the general public engaging in scientific work, or a scientist who, out of a sense of responsibility or for some other reason, puts his work and skills at the service of the community.

The reader puts down the magazine. Increasingly curious, he takes a quick online search. Somewhere, he finds that citizen science is “work undertaken by civic educators together with citizen communities to advance science, foster a broad scientific mentality, and/or encourage democratic engagement, which allows society to deal rationally with complex modern problems”. The first usage of the term seemingly traces back to somewhere in the 1970s or the 1980s. Here and there, he finds that citizen science has an increasing role in bridging and uniting science, society and policy makers. Sometimes it attracts the interest of private companies as well, looking for, perhaps, through citizen science, a way to help honour their foundational mission, contributing to common societal goals, or maybe just to greenwash their brand.

A fundamental element of citizen science is the opportunity it gives to the members of society to take up an active role in research and innovation. Citizens can actively contribute to the resolution of community problems, with the reward of witnessing the result of their efforts. Citizen science has, in addition, the increasing potential to support governments to develop evidence-based policies, at local, national and international levels.

March for science.jpg

Citizen science also helps to address tasks otherwise unattainable due to budgetary constraints related to, for example, the spatial or temporal scope of environmental monitoring. It can engage citizens to improve government’s understanding of what people value in the environment and their priorities, in order to inform environmental policy, implementation and delivery. Citizen science offers citizens the opportunity to empower themselves, contributing, in the process, to strengthen and support the social fabric. Finally, it has a potential for raising public awareness about global problems.

A particular case:

Thanks to citizen science, new know-how and capacities have been developed within specific communities. Alas, without some structures helping to integrate the generated capacities, there is a risk of missing their full impact. Successful but isolated projects may reach their objectives, but have some of their valuable lessons passing into oblivion, and part of their results lost.

Consider a community with concerns about local pollution, one of the most relevant environmental problems. The matter is put on the table, and it is noticed that no reliable local data exist. Certain informal connections between the university and local community groups exist, though. When leveraged, they enable to open a channel to discuss on the subject, with the benefit of integrating academic knowledge into the conversation. These discussions and exchanges, together with a desire to take action, result in a plan. A citizen-science project to measure the state of the pollution in the city is started; it gathers all the results, analyses them, and transmits the insights to local policy makers, who hopefully then take action.

Many communities might go through a similar process all the time, addressing the same problem or similar problems. Sometimes they don’t know where to start, and they struggle for months. Sometimes they may collect the information in a data format decided with some improvisation and without strong basis. They might find peak-pollution locations, learn about pollutant chemistry, and propose mitigating measures leading to tangible changes. Then the project stops, and their story and their results are never shared extensively outside the local community. Hundreds of ill-labelled files and databases slowly fall into oblivion in the computer of the coordinator.

Tools-bicycle-tool-vehicle-hammer-knife-electronic-140507-pxhere.com_.jpg

The communication among these communities is usually non-existent, even if it could be beneficial, as their results could be part of the solution to a more global problem. Their solutions, and their way to store the data, were independently developed, yet perhaps even similar. All managed to gather the data to answer their questions, and all were probably success stories. However, perhaps none of them foresaw how to make the data simple to re-use; and this, in practice, could render the data not easily used outside of the original project.

Making the case for data standards:

The growth and maturation of citizen science present citizens, society and governments with opportunities, but also with challenges. Citizen-science projects with differing, incompatible ways of handling data render the re-use of their data impossible or exceedingly cumbersome. This makes the spin-off of citizen-science projects from previous initiatives more difficult. The reuse of successful projects might be dismissed due to excessive implementation complexity.

Computer_brainstorming (copy).jpg

To breathe new life into existing citizen-science projects and facilitate the inception of new ones, we present one of the challenges and opportunities awaiting citizen science, and likely one of the most fundamental activities to further help citizen science thrive in the future: a shared standard for citizen-science data (and metadata).

When a citizen-science project starts, a number of things need to be considered. The underlying idea, who will participate, and the physical infrastructure and tools, may be the most obvious elements to consider. But how the information is to be collected and structured is of no lesser importance. The ways of representing and processing data and knowledge may not be visible, but still remain essential. The data structure, the “knowledge representation”, is key.

Is it desirable for citizen-science initiatives to build their data structure from scratch? Is it necessary? How many people would be capable of doing so without great difficulty? Are we reinventing the wheel with each new project? If the citizen science community were to agree on a standard way of representing and handling its data, many efforts could be saved, with potentially enormous benefits.

jumping-woman-mountain-cover-text-thank-1434831-pxhere.com_.jpg

Such standard would allow citizen-science initiatives to focus their resources on engaging the citizens, collecting observations, analysing the results, increasing outreach and solving the problem, rather than on data management. The possibility for easier project deployment and data integration would favour a leap forward in citizen science.

A woodsman was once asked, “What would you do if you had just five minutes to chop down a tree?” He answered, “I would spend the first two and a half minutes sharpening my axe.” Spending years establishing standards on data representation and handling is analogous to the sharpening of the axe. Not for chopping down any trees, but for the benefit of the whole citizen-science community, and the growth of its initiatives.

The model:

A broad initiative for the standardisation of data and metadata in citizen science was indeed initiated back in 2015. At that time, the U.S. Citizen Science Association (CSA), the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) and Australian Citizen Science Association (ACSA) founded the International Data and Metadata Working Group. The aim of this group is to promote the collaboration in citizen science through the development and improvement of international standards for data and metadata. One of the contributors towards these standards, together with CSA, ECSA and ACSA is the working group on data interoperability of the Citizen Science COST Action (CS-CA, or CA15212). The basic, standardised model (PPSR-core) underlying the standard has in fact been in development since 2013, and includes a core of key elements and concepts, which are shared by most citizen-science initiatives.

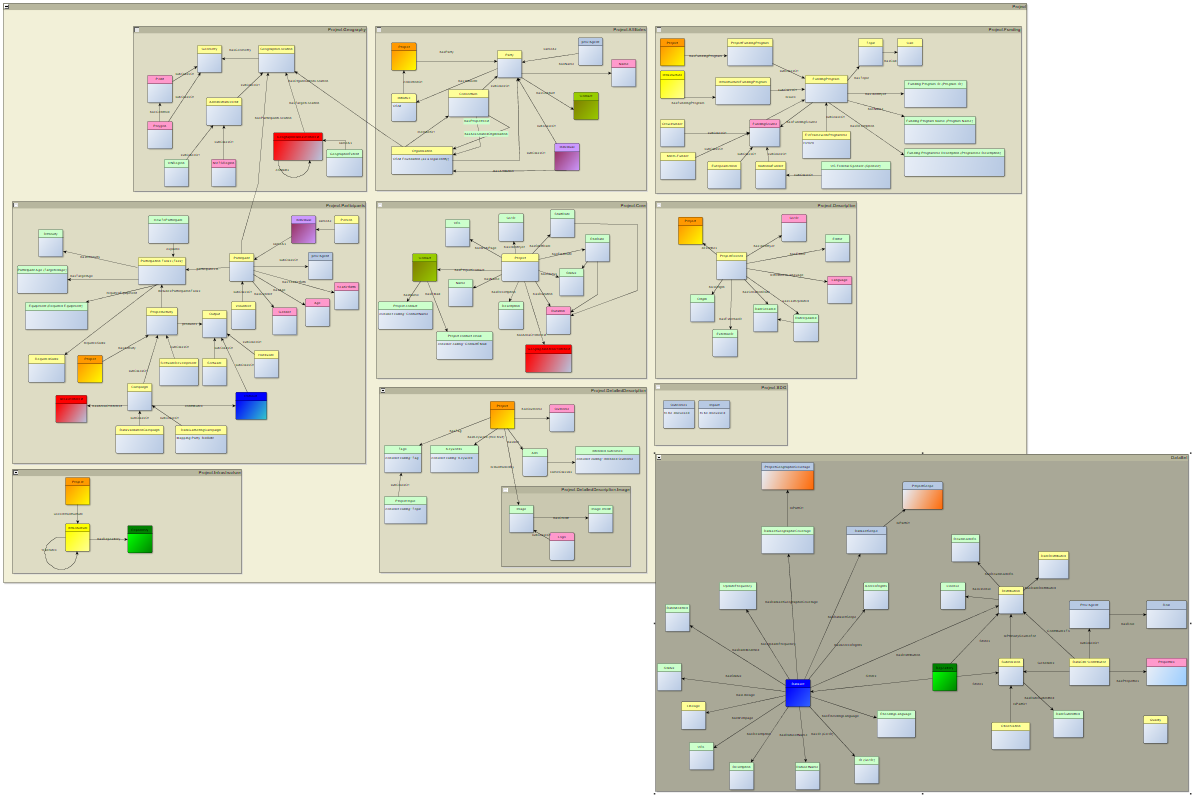

Model_overview.png

Within this initiative, a model (including a vocabulary) is being agreed on, about how to describe the core elements of the system and their relationships. The model includes information about how to represent the properties of citizen-science projects, their elements, and the properties and descriptions of the datasets storing the observations collected. The core of the model is to remain stable over time, and it will be continuously enriched with specialised modules and extensions for specific sub-fields of citizen science. The final model should ensure backward compatibility with existing major projects, and provide full documentation and clear explanations of the design principles adopted.

Uptake strategy and the importance of communication:

In line with the values of open science and citizen science, the model and its computational components will be available online (initially on the COST Action website), and published openly and royalty-free. Simple instructions on how to use the model will be provided. Scientists, managers and IT personnel in charge of a project will be supplied with the necessary information to set up the database hosting their new project.

With the model completed and launched, further support to users will come in the shape of recommendations, examples of use, tutorials, documentation, good practice policies, and guides on how to represent data in citizen science. In short, practical support and supporting material will be offered to starting citizen-science projects. Making the system easy to use will contribute to its successful adoption.

MaxPixel.freegreatpicture.com-Pieces-Of-The-Puzzle-Puzzle-Puzzles-Connection-3474637.jpg

However, ensuring the uptake of the model remains daunting. Letting communities know about the new tools at their disposal, and about their benefits, will be indispensable. The new European projects “EU-citizen.science” and “MICS” will play a facilitating role in dissemination. However, in addition to engaging the community, it will also be key to gather the support of standardisation bodies in favour of the successful uptake and deployment of the model.

Citizens and scientists: stay tuned. And, if you feel you can lend a hand, reach out!

Authors

This text was written by Karel De Pourcq and Dr. Luigi Ceccaroni.

Dr. Karel De Pourcq is the communications officer of the Citizen Science Cost Action (CA15212).

Dr. Ceccaroni is the chair of the Citizen Science Cost Action - Working Group 5: "Improve data standardization and interoperability"

Image credits:

- Front image "Binary data" taken from the public domain, by DARPA, downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.

- "Evidence-based policy" picture by Takver licensed with an Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0) license.

- "Stack of tools" picture is in the public domain, and was downloaded from Pxhere.

- "Making sense of data" picture, was modified from another picture in the public domain, downloaded from Pxhere.

- "Leap forward" picture was modified from another picture in the public domain, downloaded from Pxhere.

- "Bird's eye view" picture of data standards, modified from picture by CA15212 Working Group 5.

- "Making the pieces fit" picture taken from the public domain, and downloaded from Maxpixel.

- Text captions and images composed by Karel De Pourcq.